| Our Story - Battalion History |

|

|

|

| Recruitment into the

armed services began in earnest after the selective Service Act

of 1040 and intensified after the Pearl Harbor attack. The years 1942 and

43 were devoted to the construction of hundreds of Army camps, creating

thousands of new combat units and selection of men to fill their

ranks. With

the war in the Pacific turning in favor U.S. naval forces in the

latter part of 1942, much of 1943 was devoted to planning for the

invasion of the European continent. It was during this period of

intensity that the 82nd Engineer Combat Battalion came into

being.....our story continues! |

| The account that follows is

taken from the official history of the battalion, other published

historical documents and from my recollection of events. As with

most support units, the 82nd's line companies were often on separate

missions. Personal reflections are my experiences while serving

with Company B! Ed. Husted, historian |

| In the Beginning The 82nd Engineer Combat Regiment was

authorized as a unit of the United States Army on December 19, 1942 and act- ivated in January

1943 at Camp Swift, Texas. Although recruits arrived from across the nation, New York ( I was

inducted at Ft. Niagara), Pennsylvania and

Louisiana seemed to dominate the unit. Training began

as the 82nd Engineer Combat Regiment but

under the army's reorganization plan of March 1943, engineer

regiments were organized into engineer combat groups

and the regiment’s battalions became separate units. The

first battalion remained designated as the 82nd Engineer Combat Battalion, and second battalion as the

291st E.C.B. Regimental headquarters became the nucleus of the the 1115th Engineer Combat

Group.

The 82nd traveled to Louisiana for maneuvers on August 23, 1943 but within a few days orders were received to prepare for overseas service. Returning to Camp Swift on September 13th, the battalion spent the next several weeks obtaining additional equipment and troop replacements. Then a series of confusing orders began. On October 24th orders were received designating Hampton Roads, Virginia or Los Angeles, California as ports of embarkation. The next day, October 25th, orders were received assigning the 82nd to the Los Angeles port. The battalion’s equipment, accompanied by the supply officer and assistant supply sergeant, sailed for India, the battalion’s original destination, on November 3, 1943. |

| A few days later the battalion received it’s formal orders to prepare for movement. At the railroad depot in nearby Bastrop Texas, we boarded a very lengthy troop train. The train was blacked out throughout the trip. Drawn window shades were ordered to stay closed but an occasional peek, as we entered train stations along the way, confirmed that we were traveling East. After a bit over two days we arrived at Camp Patrick Henry, Virginia. |

| Overseas We sailed on November 23, 1943 from

Hampton Roads, Virginia aboard the Liberty ships Conrad Weiser and the

John Banvard as part of a 65 ship merchant convoy, accompanied by 20

naval destroyers. Our convoy sailed south around the Bahamian Islands, then

northeast to the Strait of Gibralter. Although initially ordered to

India our battalion, upon

arrival in Oran Algiers Africa, was assigned to the European Theater of

Operations. Because of

a lack of equip- ment, training was limited to marches in the

countryside. The Arab culture and living conditions, in the cities

and towns we marched through, was quite a shock to most of us. Then

stench of urine and filth peremeated the air. Arabs were constantly

penetrating our camp area to barter for articles of clothing.

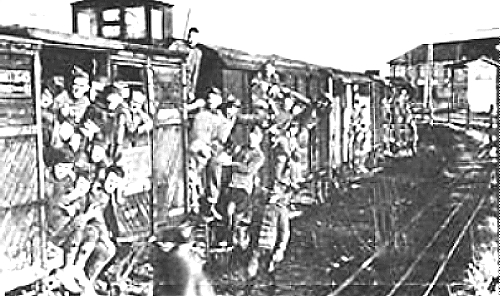

On January 5, 1944, just 22 days after arrival in Africa, we were again ordered to prepare for movement. This time we boarded a train, unlike anything we had experienced before. It was a legendary 40&8 (40 men or 8 horses) train made up of small boxcars and a slow moving locomotive that strained with every puff of smoke. While officers fared a bit better, Enlisted men were packed 30 to a car with full field equipment and rations for 3 days. Because of the crowded conditions, we slept, sitting up, in shifts, usually by leaning against the back of another G.I. for support. Our destination was Cassablanca. |

|

This trip took us over

Morroco’s Atlas mountains, a beautiful sight at

times. Relieving one’s bodily functions became a

bit of a problem, although the slow moving train made it

possible from time to time. After dismounting to heed natures

call the GI would run a top speed to reach his car. This

difficulty was somewhat solved as we reached the half

way point of our trip. Our train came to a halt at the largest

outdoor latrine we had ever seen. Here, the army had constructed

a very large outhouse, several acres in size, with long rows of

seats and equally long rows of wooden wash basins with, of all things,

running water. The irony, of this pause in our trip, was the constant

flow of Arabs who seemed amused at our bathroom activities while,

at the same time, bartering for the cloths off our back.

At Casablanca, we spent a couple of days

in camp then boarded a converted British liner, "The HMS Andes".

Running without escort, our ship with over 5,000 troops, sailed a

zig-zag course into the north Atlantic to avoid German submarines. We

turned south, off the coast of Iceland, then on to Liverpool, England.

The 82nd arrived at

Liverpool on January 20, 1944 to the strains of a military band

and took up station at Frome, a small city in southern England. Because

our equipment had been shipped to India, our early days in

England were spent obtaining new equipment and supplies. Billets

were also hard to come by as some units, including my B Company,

were initially housed over 30 miles away at a place called Tidworh

Barracks. England can be cold and damp in the winter time. Coupled with

a lack of heat in most billets due to a shortage of fuel, caused a

steady run at sick call daily.

In February the 82nd was

attached to the 1115th Engineer Combat Group, XIX Corps, United States

1st Army. Once billeting and equipment problems were solved, our

days were spent in additional combat training. On May 22, 1944 the

battalion was ordered to bivouac at Hindon Wilshire and prepare for

overseas movement.. Equipment was checked many times over,

vehicles were waterproofed and command officers were briefed on the

battalion's role in the coming invasion. The 82nd, as we prepared for

cross channel orders, consisted of 662 men; 28 officers, three warrant

officers and 632 enlisted personnel.

|

|

Our War begins (Normandy) First units of the 82nd, which included my Company B, touched down on Omaha Beach late in the day of June 16th. Earlier that morning we had boarded a liberty ship, the "JD. Ross". It was sometime in mid -afternoon when we broke over the horizon and headed toward the beach. The channel was full of ships...as far as the eye could see. Overhead, barrage balloons tethered to ships below, filled the sky. We were still quite far out when the "Ross" dropped anchor. Soon the order came to board the landing craft below. Access was down a large rope ladder where choppy seas made the decent quite a feat. Our landing craft, coming in as close as possible to avoid grounding and stopped about 100 yards off shore. We boarded our vehicles, which had been off loaded earlier, and drove down the ramp into the water. Now, the hours spent waterproofing vehicles paid off. Once on dry land, a Beach Master was frantically waving our convoy upand over the hill ahead. The beach was jammed with vehicles, equipment and stockpiles of supplies awaiting transport inland. As we crossed the beach the bodies of dead GI’s laid out for transport were clearly visible. A bit unnerving, to say the least! |

|

|

|

We drove off the beach

and up the steep slopes that characterized Omaha, over a hastily built

road. Our battalion was directed inland several miles. We entered an

open hedgerow field, but before we did so, we dragged the field for

trip-wires. Once satisfied that the area was not mined we set up a

bivouac.

(Within hours a severe storm began

whipping across the English Channel. Disembarkment of additional

troops, including most of the 82nd was halted. Many boats were damaged

or sunk and docking facilities were destroyed. The storm

practically halted the

delivery of Ammunition and fuel at a very critical time. It was

June 25th before full scale resupply was resumed.)

The first night was

chilling for a bunch of civilian boys now in a war zone. We could hear

artillery explosions but we had no idea just where we were. Our

CO. ordered outposts around the perimeter of our area. As

sergeant of the guard that night, I recall peering in to he

darkness with the men on guard. If you stare in the darkness long

enough you come to believe that something is moving out there. We

maintained our cool however, and by daylight we realized that

we were still several miles from the front lines. Since most of

our battalion was still onboard ship, we had to sustain ourselves

with the rations we carried in our pack. After several days we were

down to our emergency chocolate bar. As luck would have it, that

same day we made contact with Headquarters of the 1115th Engineer

Combat Group and received more supplies. Although not yet a full

battalion, we were assigned to support the 29th Infantry

Division. Their primary target was the City of St. Lo.

After the seas

subsided, around the 25th the rest of the 82nd began to arrive on

shore, but It was July 4th before the entire battalion could be

assembled in one area. Our written history tells us that our assembly

area was 300 yards south of the Village of Govin. Our

battalion’s primary mission was to remove mines, open supply

routes, construct bridges, establish water points and a myriad of other

engineering duties. Because of the confined area of the beachhead, our

battalion was under constant artillery and mortar attacks. Foxholes

became our home. I recall that we were visited everyday, about

dusk, by “bed check Charlie,” German spotter planes flying

low to find artillery targets. We never fired on them and hoped our

camouflage was good enough. Occasionaly a plane would find us. During

the day, as we worked the roads and swept for mines, we were constanrly

harassed by motar rounds. I always had the uncanny feeling that

enemy spotters were watching out every move.

During our

association's reunions a number of stories relating to those

early days surfaced. One man related how he hung his field jacked

outside his foxhoel and it became riddled with schrapnel. I also

recall a devout Jewish lad who insisted on standing outside of his

foxhole to conduct his evening prayers. It took considerable pleading

to get him to take cover. Another memory I have, was the local

beverage,Calvados. This drink, a clear liquid, must have been at least

150 proof....... so powerful we could use it in our cigarette lighters

where it produced a pretty blue flame. One man re- members

drinking Cavaldos and falling assleep in his foxhole. During the night

a bomb dropped nearby, didn't awaken him, but in the morning his canvas

cover had blown away and he was turned around in his foxhole.

|

| The

Hedgerows and St. Lo These early days were a learning

experience. We came to know the sounds of incoming fire and how to dig

in and cam- ouflage our bivouac area. When on assignment we

learned caution to avoid mines and trip wires. Our battalion managed to

avoid casualties until July 13-16. During this time the battalion,

while in support of the 29th Division’s drive to capture the City

of St. Lo, suffered it’s first battle casualties, one

killed and seven wounded. Artillery and mortar fire was ex- tremely

heavy as the Germans resisted the St. Lo attack. The landscape in

Normandy was mostly agriculture with farmers fields about 200 feet or

more in both directions, separated by earthen walls, called" bocage"

by the French, hedgerows by the military. These earthen

embankments were about four feet high topped by another ten

feet of bush like foliage. This, of course, gave the enemy a strong

defensive advantage. Attacking through these hedgerows became infantry

slugfest! Daily progress was measured by the number of hedgerows

taken and, on some days, the number lost!

It was here that the 82nd first took up

positions on the front lines. Our mission that day, was to blow

openings in the hedgerows to give the tanks an opportunity to fire on

the enemy behind the next hedgerow. Earlier we had prepared 50 pound

boxes of TNT for planting against the hedgerow. We moved in

during the early morning darkness and began to dig in, it was

relatively quiet. We could hear artillery in the distance but none in

our area. Suddenly, about daybreak, artillery and mortars began to rain

in. The fire was extremely heavy, keeping us hunkered down to avoid

being hit. I could hear the shrapnel tearing into the bushes over my

head and the soldier next to me, whose rifle stock was

splintered, didn’t get a scratch. At one point a vehicle

was spotted driving into enemy territory. One of our men,

Pvt. Albert Grecio, who was

located near the opening to the road, volunteered to warn the

driver. He was hit and killed. Another man also near the

opening near the rose up, ostensibly to help his

buddie, and was immediately hit. The fire continued for hours.

Later that day we were ordered to withdraw.

A lesson learned here, was that explosives alone could not open the tangled embankment of the hedgerow. After that, tanks were fitted with protruding steel spikes that could bore in and lift the earth. In the ensuing days 6 more men were

wounded by artillery as we worked to keep supply roads open.

Finally, on July 18th after days of bombing and

artillery strikes, a combat command unit of the 29th Division fought

it’s way into St. Lo under a hail of enemy artillery. . The city

was virtually destroyed. Following the city’s capture the

division, which had been on line for 43 days, was relieved by the

35th Infantry and pulled back for a short rest. The 82nd was assigned

to support of the 35th.

|

| The Breakout On July 24th we were bivouaced near

the city of St.Lo. On that morning we witnessed the arrival of

hundreds of planes heading over German Lines to lead Operation Cobra,

the breakout from hedgerow country. On our right, the 30th Infantry was

poised to attack following the bombing raid. Unknown to us at

the time, the main body of bombers had been recalled and rescheduled

for the following day because some ground units had not achieved their

objectives. The recall did not reach all planes and bombs were

accidentally dropped on 30th InfantryDivision troops killing 29

and wounding 150 men.

Reeling from this tragedy, Major General, Leslie McNair was ordered in to investigate the liaison between ground troops and the Air Force, to prevent another such accident. Under clear skies on the morning of July 25th we again came under an umbrella of hundreds of planes as the Air Force began their bombing runs on schedule. Target areas were marked by smoke bombs. Again disaster lurked, as the wind forced some smoke back over American lines. To the shock of those on the ground, some planes were unloading on the 30th Division once again. This time 64 men, including General McNair, were killed, 374 were wounded and 60 men were reported missing when it was over. In less than 24 hours 657 American troops had been killed or wounded from friendly fire! (This story was suprssed for a very lomg time!) The saturation bombing attack continued against German positions for over five hours. Although we were several miles from the target area, the ground trembled from impact. Two days later the 82nd, supported by the

234th Combat Engineers and the 992 Treadway Bridge C, was assigned

the mission of constructing bridges across the Vire River, south

of St. Lo near the village of Candol, to launch the, now rested, 29th

into the breakout area. As the battalion moved toward St. Lo, in the

early morning of July 28th, we came under a severe air attack and

were forced to de-truck and proceed through the city on foot. I recall

climbing over still smoking, debris, to reach the bridge site.

|

| Company B was assigned security at the

bridge site. I recall that, as we set up our gun emplacements, we

kept hearing noise coming from the other side of our position. As I

crawled through the foliage to find the source, I encountered a 35th

Division mortar section firing furiously

at targets beyond the next hedgerow. It was nice to

know we were in good company. At 900 hours construction of the

first of two bridges began. Within hours traffic was moving and command

ordered the construction of a second bridge to accommodate the heavy

traffic. Only one casualty was recorded during the air raid. During the week after crossing the Vire River, we devoted our attention to mine sweeping and maintaining supply lines, through the French towns of Moyen and Chevry. Company A constructed a bridge over the Drome River at Chevry. |

| The Battle for Vire At 2300 hours on August 4th the

battalion was ordered in support of the Second Armored and 29th

Infantry Divisions in their drive to capture the city of Vire

France. Our mission was to support both divisions, first to clear

the approach roads of mines and then to enter and open the

roadways in the city. Vire was in shambles and streets were

loaded with debris. The battle

for Vire was fierce as the Germans, occupying high ground, unleashed a

steady barrage of artillery and mortar fire.

The attack began on August 5th, as Units of the Second Armored Division led the initial assault with 20 tanks, attempting to enter the city from the north. Very accurate fire from German artillery destroyed 14 tanks causing heavy casualties. It was quickly concluded that it would require infantry to gain a foothold in the town. The next day August 6th, 29th Division infantry, in the early morning darkness and facing direct small arms and motar fire, scaled the hillside on the western edge of the city. The next morning the 82nd was ordered into the city to open major routes to permit armor and artillery to take up positions south of the city. |

| (Here is my

recollection of one of B Company’s assignments during this

mission.) We assembled that morning perhaps a half mile from the City. Our assignment was to clear the streets of mines and rubble. It was just breaking day when we approached the city on foot, up a fairly steep hill and headed toward a Bridge over the Vire Rive. Once on top of the grade, we moved through a narrow street with milti- story buildings on each side providing cover. As we reached the end of the buildings and started across the bridge, machine gun fire came from both sides of the bridge. I saw the officer in front of me fall. I thought he had been shot. By a miracle, he had hit the ground without a scratch. Since the enemy was still very much in control, the call went out for artillery strikes. As we moved back down the road, to give the artillery an open target, we again came under machine gun fire from a ridge ahead of us. Bullets were kicking up the road dust toward the platoon leaders jeep. The same officer, who avoided a bullet earlier, was seriously wounded this time, as bullets raked his jeep. Realizing we were cut off, I remember another officer saying " we've got to get that gun. We formed a skirmish line and started up the hill toward the gun. We were probably a couple of hundred feet into the woods when artillery and mortars began exploding all around us. I recall that we ran to a building several hundred feet away for cover. Vivid in my memory is the very loud explosions. This area was a bit like a valley with high ground on each side. Every shell that hit was not only loud but echoed off the surrounding hillsides. The air virtually shook as these shells exploded around us. When the fire lifted, and as we headed toward the gun emplacement again, we confronted an 82nd officer, Lt. Wilbert White, walking toward us from the direction of the roadblock. In a pronounced Texas drawl he said" You boys got a problem?" The tension was broken. Other units, realizing our problem, had taken the guns out. Inspecting the jeep we found that bullets had traveled up the seats. The jeep driver, a tall kid from Louisana, managed to clear his seat...the officer was not so lucky! |

|

|

|

Once in the

city, the Germans kept slamming our guys with

artillery and sniper fire. By August 9th we had cleared all

roads in our sector. With the completion of our mission we

were relieved by the 295th Combat Engineers and moved back for a rest

and resupply. During the mission two of our men, T/5 James Teed

and Pvt. Sam Holland were killed and another

15 wounded by artillery and sniper fire. The prisoner count, at the end

of the mission, totaled 128. Our battalion was awarded the

"French Croix De Guerre"(cross of war) for this mission.

( In 1995 I had the opportunity to revisit Vire and stand in the very spots where we were raked with gunfire over a half century ago. Most of the buildings look just as they did in 1944. ) |

| Turning East Up to this time we had been moving south,

away from the beach. Allied command had earlier selected Vire as

the pivot on which all armies would begin a swing eastward toward the

Seine River. At this time the boundry between American and

British forces ran along the eastern outskirts of the city. On our

right the VII Corps was beginning their swing eastward and on our left

the V Corps was already attacking toward Arganten. Meanwhile

British and Canadian troops were attack- ing south toward the City of

Falaise. In this pocket, between Argantan and Falaise, the German

Army was being com- pressed and destroyed. The carnage and

destruction in that pocket was unbelievable. Thousands of dead

troops, horses & livestock and hundreds of tanks,vehicles

and artillery pieces, littered and clogged every road and

field.

As flank units began their turn eastward, the XIX Corps was squeezed out of the line. Our Corps was ordered to move in a northeasterly direction, with all possible speed, to cut the enemy off at the Seine. The 82nd began it’s move on August 15th with the longest motor march since landing, covering 30 miles, to bivouac near Barenton. In succeeding days we made a series of long motor marches. Although there was little enemy resistance, seven of our men were wounded by land mines and booby traps during the move, While the Corps's move was completed in record time, a large number of German troops managed to escape across the river, although most did so without equipment of supplies. |

| At the Seine We arrived at the the French city of

Brevel, near the Seine River, on August 26, 1944. Two days later Company B was detached

from the battalion and assigned to the 113th Cavalry Group.

History records that Eisenhower’s original battle plan was

to hold at the Seine River, to allow Supplies, particularly gasoline

and ammunition, to catch up with the attack- ing troops. With the

Germans on the run, it was decided to continue the push to

the German border. With gasoline in short

supply, the mission, in our Corps area, was handed over to

the 113th Cavalry Group. Orders were to move as

rapidly as possible to prevent a German stand short

of their homeland.

Now attached to the 113th, we crossed the Seine River over a partially damaged bridge at the village of Le Pecq, about 12 miles north of Paris, in the early the morning of August 29th and into the Commune of Le Vesinet on the far side. These two communities are part of the greater Paris region. The Germans had made an attempt to destroy the bridge but only succeeded in blowing a hole through the decking. In the early morning hours of darkness a section of bridging was placed across the damaged area by another engineer unit and the 82nd was rolling. We were the first Troops to cross the Seine at this point As we touched down the far side we were greeted by about thousand, cheering, screaming civilians, including many wearing FFI armbands (the underground resistance). The crowd surged up to our vehicles, shouting and reaching out to touch our hands. I remember a very tall man, wearing a tam, shouting in excellent American profanity, how grateful they were to see us and advising us that the Germans had just left using every means of transportation available including bicycles and horses. I learned that this man was an American soldier from WW I, who took a bride and settled in France. I also remember some members of the FFI begging us for guns and ammunition so they could conduct their own war on the Germans While the 2nd and 3rd platoons of Company

B, moved through Le Vesinet with the lead Cavalry, My platoon,

the 1st, was held in reserve. We set up bivouac in a park in the

center of town. I would be remiss if I didn’t reflect on the this

brief respite. Le Vesinet had not been damaged and we could mix

freely with the civilians, especially some very pretty girls. Soon

after setting up camp, another GI and I were approached by a

representative of the FFI who ask if we would be their guests at

a liberation party that evening. After making sure we would not be

moving out that day, we accepted. When we entered the room that

night it was clear that we would be the only American soldiers

there....we were representing the entire United Stated Army. This

is one party I will never forget. Food, wine, music, dancing, and an

endless series of toasts to us, their liberators!

(In 1995 I had the opportunity to stand in front of that very building, which looked to me just as it did over 50 years ago!) Meanwhile the rest of our battalion (A&C) had arrived at the Seine River at Muelan, about 23 miles further downstream, and prepared to bridge the river. Infantry had moved in from a downstream bridgehead to secure the area across from the bridge site. At 800 hours on August 29th, A& C companies, supported by the 17th Armored Engineers, began con- struction of a treadway bridge to provide a XIX Corps supply route into Northern France. The infantry was immediately engaged by enemy troops. With heavy fighting taking place in the bridgehead and artillery landing in the launching area bridge work was temporatily halted. Despite the problems work resumed and the bridge was opened for traffic at 1800 hours the same day. |

| On

the Run In preparing for the invasion of France, planners envisioned that one or more of the channel ports would be in operation by this time. As they retreated, the Germans were causing serious damage to all port facilities. Although the Red Ball Express, which consisted of never ending column’s of trucks carrying supplies from the Normandy beach area, was infull swing it was not sufficient to support the ever widening front. Tanks alone, consumed thousands of gallons of gasoline daily and the trucks shuttling supplies to the front thousands more. Consequently, upon reaching the Seine River, supplies of gasoline and ammunition were in critically short supply. As related earlier, to keep pressure on the the enemy, General Eisenhower ordered fuel priority be given to fast moving recon units, such as the 113th Cavalry, to whom we were attached, with the mission of reaching the German border as fast as possible. Armor and infantry units would follow several days later. After a brief 48 hour stop in Le Vesinet our 1st Platoon headed north to join the lead columns. |

| Moving rapidly our cavalry led column

by-passed major pockets of resistance, veering off the main roads onto

secondary roads every couple of hours. I recall marveling that

the map reader, who was guiding our column, was doing a whale of a

job. Each time we encountered German positions he found a side

road around the roadblock. Although the armor and Infantry

following us would clean up these pockets, we still had work to

do. Our battalion ran into enemy fire a number of times. Near the Belgium town of Wavre, B

Company’s 2nd platoon was attacked. Pvt. Al Marks was

killed

and several vehicles destroyed in this engagement. . At

Gembloux Belgium

a group of men from Company C became engaged in a firefight.

Although the Germans had offered a white flag of surrender, as S/Sgt.

Carl Lietzke moved in to disarm them, rifle fire

continued. Sgt. Lietzke was killed and another man wounded.

A few days later, upon reaching the Belgium town of Kesselt on the Albert Canal, a patrol from B Company’s 3rd platoon, working near the Canal to locate possible crossing sites, was attacked by an enemy ambush. In the resulting action Cpl Richard Wells was killed, another man wounded and and three taken prisoner. |

| By September 9th the

west side of the Albert Canal, which separates Belgium and The

Netherlands, was secure. Along the way we captured 132 prisoners, so

many, that we simply disarmed them and sent them back along the road.

Some- where down the line MP’s would hustle them into a

stockade. |

| With the Germans well entrenched on the east side of the Albert Canal in this sector the cavalry unit split , with one column crossing the Albert Canal northward in an area under British control and a second column, with Company B, heading south to cross the Meuse River in the VII Corps sector at Leige Belgium. Entering Leige was memorable, as thousands of screaming people lined the streets to greet us. I recall leaning out from the passenger side of our squad truck and touching a couple of thousand outstretched hands. In the back of the trucks our guys were bombarded with bottles of wine, fruit and flowers. It is hard to describe the elation that was felt by everyone that day. |

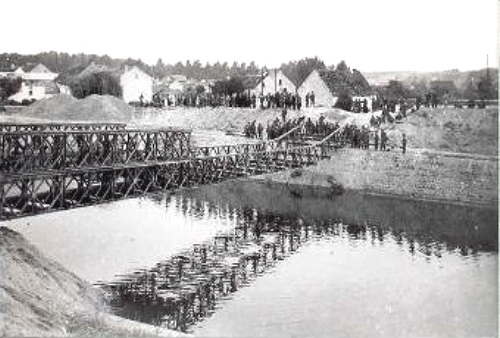

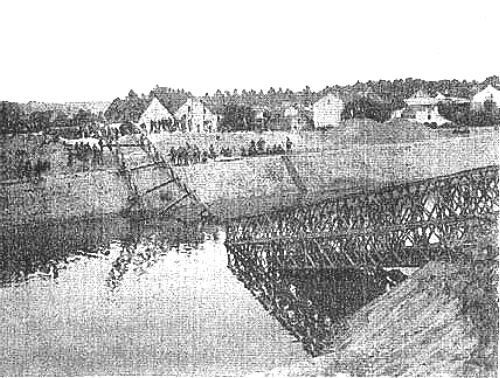

| Once across the river, our column pressed

the attack northward into southern Holland. With the 113th

Cavalry Group, we fanned out to liberate towns throughout southern

Holland. The enemy was engaged at Gulpen, Berg, Papenhoven,

Illkhoven and Roostern and other hamlets along the way. Six men were

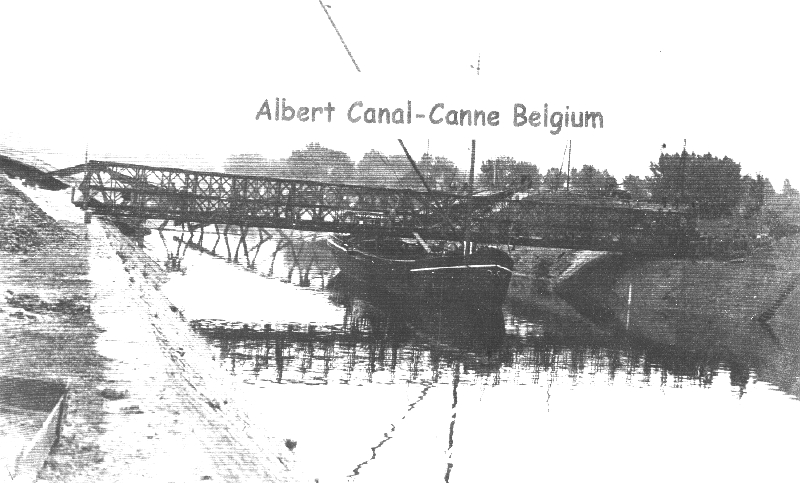

wounded during these missions. Meanwhile, the rest of the battalion ( A&C companies) crossed the Seine at Meulan and traveled a route parallel with that of company B, clearing roads, repairing bridges, and taking prisoners. Upon reaching the Albert Canal, on Sept 12th, they found all bridges had been blown. The next day the battalion was given the mission of constructing a Baily Bridge across the canal at the village of Kanne (see the XIX Corp Engineer's mission report ) . With elements of the 2nd Armored Division waiting to cross, initial attempts to push the140 foot Bailey Bridge across the canal, resulted in the collapse of the far end of the structure. Needless to say there was considerable anguish in 82nd command and we can be sure, substantial irritation at Second Armored headquarters, during this time. We are fortunate that someone had the foresight to record this minor disaster. (see below) |

|

|

|

|

|

| Undaunted,

the bridge was pulled back, repaired and re-launched late the

next day, September 15th. The armor then, raced across the narrow

throat of Southern Holland toward the German border. The battalion

(less Company B) moved across the canal to bivouac at Aalbeek Holland. On October 1st Company B, with Cavalry units, first entered Hitler’s fatherland at Tuddern Germany. The 113th’s mission was to capture three German villages just across the border. The 82nd’s task was to secure a still standing bridge then move in, occupy, and secure the villages once captured. I remember the scene as we arrived down a narrow country road. Directly in front of us was a concrete bridge (our assignment) spanning a shallow stream. On our left, along the stream, was a large barn which became our command center. To the right of the road the 113th had light tanks lined up facing the creek. Enemy troops were estimated at no more than three hundred so the attack seemed like a slam dunk. I also remember that mortars began popping soon after we set up bivouac. We set up our gun emplacements covering the bridge at dusk. During the night a German patrol attempted to enter our lines. Two of our men were wounded but their was no retaliation in force by the Germans in our sector. The attack, led by an attached tank battalion with a company of infantry, kicked off at 900 hours the next morning. They immediately ran headlong into a well entrenched, enemy force, firing 88 MM shells directly into the tank column. Although the task force column tried several times to push their attack, they were driven back by heavy fire. Less than two hours later, the loss of firepower and heavy casualties brought the attack to a halt. The mission was then aborted in favor of more armor and infantry to follow. During these two days, Company B suffered 11 casualties with two men, Pvt. Sal Russo and George Lucey missing in action. (The bodies of these men were not discovered until 1947. It is assumed that they were killed by the heavy artillery shelling endured during the mission). |

|

Supporting the

British

On September 27th the battalion (A & C Companies) was attached to the 7th Armored Division. Two days later all units moved north 78 miles, through a British held corridor near Eidenhoven, to bivouac at St Anthonis Holland. This mission was to assist the British in pushing the Germans south and east, back across the Muse River. The 7th’s immediate target was the city of Overloon just a few miles to the south of St. Anthonis. The 82nd set up and occupied defensive positions in former German trenches, constructed a treadway bridge and removed and laid mines. While laying a defensive mine- field, a squad from Co. A came under German fire. First, T/5 George Sanders, was killed by an exploding mine then, alerted to the mine laying activity, the Germans laid in machine gun and mortar fire seriously wounding the three other men in the mine laying party. Although documentation is lacking, PfC Charles Piltzecker was wounded during this time. He died several months later while in the hospital. The 7th Armored Division’s assault was cut down by heavy German fire. Tanks were being destroyed as fast as they emerged from deep wooded areas to launch the attack. Since they could not could not penetrate this fierce German resistance, the mission was suspended on October 6th. British command decided to implement a different attack plan. The 82nd moved back to base at Aalbeek Holland on October 8th. After 37 days with the Cavalry, Company B was detached from the 113th and rejoined the battalion at Aalbeek. |

| Crossing

the Border Our battalion with all companies

intact, formally crossed into Germany on October 11th, to bivouac

at Sherpenseel,a small town just inside the border. The 82nd was again

placed in support of the 2nd Armored Division, who was engaged in

attacking German Seigfred line fortifications. It had now been 122 days

since landing in Normandy and the Rhine River was only 40 miles away.

Cautious feelings that the war might soon end

were dashed shortly after crossing into Germany.The first obstacle,

the infamous Seigfried line, was quickly breached by Armor and

engineers who covered the concrete anti-tank barriers with earth

allowing traffic to drive across the top of the obstacles. The

82nd moved through the line on October 12, 1944. As as the month

wore on however, it became clear that the enemy had

prepared defenses well and had either visual or prepared artillery

targets. Before the month was over 10 more men, wounded by

scattered mortar and artillery barrages, were added to the

battalion’s casualty count.

With the allied front now widening rapidly, another army command was added to the line. On October 22nd the Ninth Army, newly arrived from action in Brittany, was inserted between the First Army and the British Second Army to the north. The 82nd, with the XIX Corps, was transferer to the Ninth Army. At this time we were rubbing elbows with our British counterparts. |

| The next

major objective was the Roer River just 15 miles to the east. During

November and early December the 82nd was engaged in extensive mine

removal and road repairs, slowly working our way toward the

river. As the Germans retreated across the Roer, they established fire

patterns that blanketed approaches to the river. This confined

area, together with numerous mine fields, caused battalion casualties

to mount rapidly. On November 17, A mortar barrage hit a squad of

men who were sweeping a road for mines. Pvt. Norman Fotch , Pvt.

Charles Houser and Pvt. Ted Isaacs were killed and 9 other

men wounded. On the 22nd, Pfc Roy Kennedy and

T/3 Ken Taber were killed and two other men wounded by shellfire.

The following day, Lieutenant Richard Frey and

Joseph Campanale were killed and three others wounded

by a mine explosion. Upon reaching the Roer, about December 12th, we began preparations for bridging the river. The Germans still controlled large up-stream dams,constructed years before to flood the Roer Valley as a defensive measure. First Division troops attacking toward the dams were experiencing fierce resistance. The Roer crossing was being held, pending control of the dams. |

| The German Counter Offensive ( The Battle of the Bulge) As we prepared for bridging the Roer, word

came on December 16th that the Germans had launched a counter attack

south of our positions. As the hours progressed it became clear that

this was a major assault, which would later be known as

the" battle of the Bulge." Five divisions from

our XIX Corps sector were transferred south

to help stem the German breakthrough. Because the German

attack had split General Bradley’s 12th Army Group, we were

placed under the command of the British 21st Army

Group....General Montgomery. Front lines in this sector were now thinly

held. The Germans continued to pound our area with very accurate fire

and we continued to sweep for mines and repair the roads torn up by

artillery strikes. Our casualties continued to mount. On

December 17th Company C was again hit by mortar barrage. Pvt.

Martin Berry was killed and several others wounded.

Overall, November

and December had been costly as 45 men were killed or wounded by mines

and constant shelling. As the

new year began snow and frozen

ground made road maintenance and the removal of mines difficult

and dangerous. Also, during this time, the 82nd, along with other

special- ized units, operated as front line infantry in the XIX Corps

sector.

On January 23rd we relieved the 234th Engineers, taking up front line positions in the vicinity of Billstein and Winden, Germany. On our far left the 29th Division was holding position in front of the city of Julich. The 113th Cavalry was on our immediate left. To our right the 8th Infantry Division anchored the line in our sector. We were assigned to a large multi- story stone structure, with thick walls and a series of openings reminiscent of a castle, overlooking the Roer River. The weather was cold and the ground covered with snow. We could actually see the Germans posting guards from time to time. Action was limited to artillery barrages which continually cut communication lines, but bounced off the walls of this imposing structure. We sent out patrols nightly and on one occasion, crossed the river (only about 80 feet wide at this time) to take prisoners but the Germans had slipped away. Our history records two men wounded at this building but a number of men wounded by artillery in our service areas to the rear. |

|

Mission on the Roer

By January 15th the bulge in Allied

lines had been eliminated and the war was back on a more predictable

course. On February 4th , the 82nd was placed in support of the 30th

Infantry Division and ordered to construct two bridges across the Roer

River near the villages of Pier and Shophoven. A serious problem

existed however, as the Germans still controlled two

large upstream dams, that had been constructed years before for just

such a situation. First army troops to our south had been battling

for weeks to reach the dams, before the Germans

could unleach a wall of water down the river. In anticipation of

a successful attack to seize the dams our mission was set for

February 10th. I recall working on the approach roads and

stockpiling equipment. I also recall that we dug a 6 foot

command center overlooking the river, for the battalion commander to

oversee the bridging operation.

On the 9th it happened! The

afternoon before we were to begin the bridging operation, a wall of

water cascaded down the the river. About 80 feet wide in normal

times, the entire valley was now inundated. Although First

Army troops had taken the dams, the Germans had

destroyed the Control valves. A week or so later our mission was

reset for the 23rd. Although the river current was still

extremely strong, command officers evidently figured to

catch the enemy off guard by attacking before the river fully

receded.

Bridging the Roer was one of the

battalion's most difficult missions of the war. At 2 a.m. on the

morning of February 23rd a squad of men crossed the river in a

specially designed boat to secure guide cables. The trick was to take

the boat and a cable up stream as far as possible,

so once launched into the swift current,

the boat would reach the far side at the target area. No

small feat! While they made it across, artillery and small arms

drove the men into the water for cover after several had been

hit. A second try with a rope lead and cable was launched. The

boat capsized. It took four more try’s before a cable was

anchored on the far shore and the wounded men rescued. By this

time daylight was creeping in. Normally the footbridge

required two cables, every attempt to get a second

cable across failed. I recall an officer shout- ing that we would

go with one cable.

|

|

My squad’s assignment was

to guide the assembled bridge into the water, connect it to the guide

cables and feed it into the river. We experienced some shelling but it

lacked accuracy. The infantry bridgehead was keeping the German

artillery out of visual contact. This was February and we were

wading in freezing cold water. The first few minutes went smoothly

but as the bridge reached the heavy current it began

to twist. We had men riding on the end of the bridge to hook

the cables. I realized what was happening before the men on

the bridge were aware of the bridge’s movement. Over the roar of

the river, I remember screaming at the men to hang on.

Within seconds the bridge was ripping apart and the crew was struggling

to get of the current. All made it back safely. By this

time

we were all cold , wet, and disgusted, to think we had failed. Command

officere realizing we could not overcome the current in this area,

decided to move to an alternate site.

It was noon by the time we commenced the second bridge and despite the strong current we were able to attach both cables on the far shore. Bridge construction moved along much better at this location. The bridge was completed by 4 p.m. Within minutes a steady stream of 30th Division Infantry with rifles port high were racing across our bridge. We experienced a bit of an emotional high, as we greeted the infantry troops heading onto the bridge. We had just made a major contribution toward ending the war! With the footbridge complete, other 82nd units began working on a treadway bridge to get the tanks and heavy equipment into the bridgehead. This bridge was completed, the next day, February 24th, without casualties. A footnote on this bridge: lacking firm ground to anchor the cables on the near shore, a large bulldozer, partially burried in the soft earth, became the cable anchor. Our battalion moved across the Roer on

February 28th, bivouacked at Steinstrass, then began moving with

the Corps, in a northeasterly direction, toward the Rhine River. Much

of the time was spent preparing the roads for the heavy traffic that

would follow, for the assault on the Rhine River. Two bridges were

constructed, during this time, over the Erft and Nord Canals

respectively. With the Germans now being rapidly pushed

back across the Rhine, we experienced one of the few times, since

landing in Normandy,out of range of enemy guns.

|

|

|

| Breakout (Across the Rhine) The assault crossing of

the Rhine was a joint operation with British, Canadian and

Ninth Army troops. The 9th Army was again placed under the command

of British General Montgomery. While our battalion, as

a whole, was

not involved in the assault crossing, 23 men had been assigned

the special mission of assisting the 30th Division's

258th Engineers in operating boats during the river assault.

The attack in the Ninth Army sector was launched by the XVI Corps with the 30th and 79th Divisions leading the way. Commencing at 1A.M. on the morning of March 24th, one of the most intense artillery barrages of the war, pounded German positions for over an hour, as 2000 guns dropped over 65,000 rounds on on the far side of the Rhine. 82nd boat crews carried infantry motar sections across during the assault. The Rhine River is extremely wide and placed a strain on small outboard engines. One crew lost an engine to overheating, was rescued and towed back by the other boat.. Crews reported considerable artillery flashes but no rounds found their mark. Because of the heavy artillery saturation a bridgehead was quickly secured with minimal casualites. As soon as the Assault troops reached the far shore, division engineers began construction of a floating treadway, at the City of Wesel. The XIX Corps had been given the mssion

of breaking out of the bridgehead, once across the river. The 2nd

Armored Division was selected to spearhead the attack. On March

28th the 82nd was attached and moved to the 2nd armored Division

assembly area

at Altfeld

While we were unaware at the time, a severe command conflict was taking place between 9th Army Commander, General Simpson, and British Command. Montgomery's battle plan called for the Rhine assault to be an all British mission, with Ninth Army to participate once the bridgeheads were secure. American commanders objected and Montgomery modified the plan to include 9th Army troops in the initial assault. The the rift didn't end there.....conflict flared again! Although the one bridge at Wesel was constructed by US.engineers, General Montgomery established priority for use of the bridge by allocating 18 of each 24 hours to his troops and 6 hours to American units. This directive made it impossible to get sufficient American troops across, to lead the breakout. A couple of days later, probably after some testy confrontations, Montgomery reversed the allocation in favor of the 9th Army. |

| Destination Berlin The 82nd crossed the Rhine with the armor,

about mid-day on March 29th. The next day 2nd Armor's

spearhead had reached the Dortmund Canal at Ludinghausen where all

bridges had been blown. Our battalion was ordered to bridge the

canal. At 1400 hours on the 30th, after an artillery barrage, the

2nd Armored's 41st Infantry crossed the canal, crawling over the

damaged bridge, to set up a bridgehead. A short time later, Company A

began construction of the bridge. By 4 a.m. the next

morning the armor was rolling.

|

|

Our route was taking us just north of the

Ruhr Industrial area, Germany's war production

center. Other units, including the 3rd Armored Division, were

circling around this area from the south. As we moved

rapidly eastward the 2nd Armored was split, with our main column

continuing toward the Weser River and another 2nd Armor Combat Command

swinging around the eastern side of the Ruhr. A few days later

the noose was closed as the 2nd and 3rd Armored Divisions linked

up at the city of Paddenborn. In

the meantime we continued to move East with the main body of the Second

Armored. At one time these two units were 125 miles apart. Since the

82nd was now out of communication with the 1115th Engineer Group we

were reassigned to the 1104th. Engineer Group.

On April 5th we arrived at the

village of Grass Berkel near the Weser River. All bridges had been

blown. The next day, April 6th, we moved several miles south to a

position near the village of Grohnde. Germans occupied the far shore.

Soon we learned that we would not have a bridgehead since since

the Infantry was occupied elsewhere along the river,

We had to take matters in our own hands to flush out the enemy. With assistance from the 992nd Treadway Bridge Co., we opened fire on the far shore. We were surprised when white flags began to quickly appear. We launched a patrol who returned with 26 prisoners, although quite a few more slipped away. Some had been wounded. I remember an SS officer, who had been slightly wounded, crying not because he was hurting but at the humiliation of becoming a prisoner. So much for the master race! |

Patrol launched to collect prisoners |

Weser River bridge constructed April 6, 1945 |

|

With the far shore secured, we began

construction of a 400 foot floating treadway bridge just before dark

and worked throughout the night. The armor was rolling again at

dawn. While working on the bridge in the nightime darkness

Pvt. Ed. Beall fell from the bridge and was was drown. His

body was

not recovered at that time.

In the meantime Companies A and C had

been ordered north to the village of Hameln, to assist the 1104th

Engineer Group and the 544th Heavy Pontoon Battalion in constructing a

treadway bridge at that point. Hameln, as we remember, was the

home of the legendary "Pied Piper". They experienced considerably more

resistance than we did at our site.The Germans laid in heavy small arms

and mortar fire, interruping construction for nearly 24 hours until the

bridgehead was secured. Four men from the 82nd were wounded

during this mission. Meanwhile the battalion constantly on

the move, arrived at the the village of Bantlyn on the Leine River

on April 7th , to Nette on the 8th and to Shalden on the 9th . Near

Shalden T/5 William Gettleman , a motorcycle dispatch

rider, was killed in a collision with another army vehicle.

|

| Beginning of the End (on the Elbe)

By April 11th forward elements of

the 2nd Armored Division had reached the Elbe River south of the city

of Magdeburg. We moved, with the rest of the division, into an

assembly area at Grass Ottersleben the next day. Preparations were

immediately made for 82nd to assist the 17th Armored Division

Engineers to construct a bridge across the Elbe at the village of

Wester-Husen. It was during this briefing that I recall our Co

saying “Mount up boys, we’ll be in Berlin

in 5 days". That was the plan!

To secure the bridgehead, Co. A manned assault boats to ferry the 41st Infantry across the river. Once the Infantry was deployed, our Co. C and the 17th Engineers began bridge construction. Everything proceeded well until early morning when the enemy realized what was happening and began to shell the site. German accuracy was hampered for a while, as Company A laid down a smoke screen but as the bridge neared the far shore, intensity of the artillery increased, laying direct hits on the bridge, forcing command to abandon the site shortly after mid-day. PFC William Horner, was killed in this operation. On the same day, April 13th, Pvt. Harris Hill was killed when he drove in to a German roadblock near the city of Magdeburg. |

|

Orders were then received for the 82nd to

construct a bridge and a ferry at the village of Schonebeck, a few

miles south of Wester-Husen. Before daylight the next morning

infantry pushed down from their previous bridgehead to secure the

Shonebeck area, and Company C began construction of this new

bridge. Again, the enemy was waiting. At 7:30 a.m. the Germans

launched a counterattack on 41st infantry troops holding the

bridgehead on the far shore. Shells began to land on the bridge.

Bridging parties on the near side watch as the enemy surrounded

the infantry. The fight was intense and many were forced to

surrender. Faced with motar and small arms fire and without bridgehead

protection work on this bridge was suspended.

Now it was B Company’s turn. Efforts

to get across the Elbe now centered on construction of a ferry at an

existing ferry site in the center of Shonebeck. First it was necessary

to place a 1 inch steel cable across the river to serve as a guide for

the ferry. Those who were involved in this operation will

recall the difficulty of anchoring the cable on the near side. The

area consisted of a cobblestone ramp which led into the river..... no

chance for a buried dead-man. The only anchorage available was a large

stone building which was located adjacent to the ramp. The cable

was fed through the basement window using the very thick walls of the

basement as the anchor. It worked! I have vivid memories of the

constant shelling during this operation. The shells, hitting the

cobblestone would throw shrapnel and debris in every direction,

quite different that shells hitting soft earth.

|

|

The ferry, powered by two outboard motors

and loaded with a D-7 bulldozer, made it to the far shore but grounded

in the soft mud. No chance to unload the dozer. An amphibious DUK

was sent across to free the ferry. Artillery fire had been

extremely heavy all during the operation. As the ferry began it’s

return trip, to obtain additional equipment, a direct hit snapped the

cable and disabled the outboards. I had taken cover

around the corner of a building and I recall hearing the cable

snap. As I stepped out to check on the problem I saw ferry free

floating

down the river. The current began to carry the ferry toward enemy

shore. Once again the DUK came to the rescue. The ferry was

abandon but all the men were returned safely to safely to

shore. With the bridgehead virtually destroyed, two bridges and a

ferry knocked out, all efforts

to secure a crossing in this area were abandon. As often happened, during the war, an

area just a few miles up stream was lightly defended. The 83rd

Division with our sister outfit, the 295th Combat

Engineers, managed to get a bridge across

the Elbe, at the village of Barby, without serious

resistance. With this and other completed bridges

downstream, the infantry was fanning out on the east bank of

the river.

In the meantime, a few miles to the north, the 2nd Armored and 30th Infantry Divisions were pushing into the city of Magdeburg. On April 16th, the 82nd was ordered into the city to open up vehicle routes. We moved quickly, with little indirect fire, to open access to the river. Within three days Magdeburg was securely in American hands and traffic was moving. |

|

On April 17, 1945 the

82nd Engineer Combat Battalion received its last combat assignments.

Co. B was ordered to take over security of the 83rd Division bridge at

Barby, while A and C companies were assignd bridge security on the

Salle River. There were two Elbe River bridges in this

vicinity, one called the Roosevelt Bridge and the other the

Truman Bridge, our assignment. The Germans in a last

ditch effort, made several attempts to demolish the Barby bridge.

First, a floating mine struck the bridge knocking out one float.

A few days later an enemy frogman tried to blow the bridge. His

charge floated under the bridge then exploded as it hit the shore

causing more damage. The swimmer was captured. Finally,

a lone plane bombed and strafed the bridge. I recall

this incident clearly. I had just started across the bridge

to join my squad on the other side when I saw tracer bullets slamming

into the bridge ahead of me. I turned and ran to the shore

diving under a large crane that had been used to set the

treadways. As I hit the ground a bomb exploded very close to

me, followed by a second bomb, all missing the bridge and

me. Remembering that I did not hear the plane approaching

before seeing those tracers, I realized we had seen our first jet

airplane.

Up to this time,

we had been led to believe that our ultimate goal was Berlin. We

realized we were now in a holding pattern and reports were surfacing

that Soviet troops were approaching the Elbe River from the

east. In hindsight, It’s interest- ing to note that

most command officers had Berlin firmly affixed as our

ultimate goal. History shows that the decision to save Allied

lives and let the Russians fight for Berlin was General

Eisenhower’s alone and he, obviously, didn't share his

decision with other command officers until the very end.

|

Our war

is over

At last the shooting stopped in the

battalion’s sector. Thousands of Germans were laying down their

arms and surrender- ing, with hundreds coming through our lines during

the month of April. On May 6, 1945, the 82nd was directed to to cease

operations and ordered out of the line. Two days later came the

formal announcement of the war’s end. A total of 336

days had passed since Normandy...... Our war, 326 days!

We loaded our equipment and began

immediately to move out of the area for return to Normandy.

Although the shooting had stopped, the 82nd took more casualties.

On a wet cobblestone road, a truck carrying a large bulldozer was

struck by a passing jeep. The dozer flipped off the truck pinning

and seriously injuring two men. A couple of days later two more

men

were wounded when they encountered a booby trap mine.

(While we were on the road, on may 9th, I was granted a seven day leave to a G I rest center in southern France. While I was basking in the Mediterranean sunshine, the battalion took up station at Camp Twenty Grand which was located near Le Harve. I developed a set of bad tonsils while on leave, was hospitalized, and didn’t return to the 82nd until about June 1st.) In early June, while in Rouen France, we

received

word that would that would bring an end to the 82nd’s current

organization!

To facilitate the return of over five million men who had entered the E.T.O since D-Day, the army devised a point system, based primarily on length of service. The 82nd Engineer Combat Battalion was designated to receive men who had higher discharge points, for early return to the States The majority of us, now serving with the 82nd, had not accumulated sufficient points so we were transferred to other units. (In my case; I was transferred to Epernay, France and assigned to the 3051st Amphibious. Engineers as a platoon sergeant. One of the officers, A captain that I knew, also from the 82nd, became my new CO. I recall clearly our first briefing. He told us that upon the reorganization of the 3051st we would be sent back to the states for a 30 day leave, more training, and deployment to the Pacific. He ended the briefing by saying " Frankly Gentlemen we're going to hit the beaches in Japan". Not good News!) As the days extended into August,

reorganization of the unit was now virtually complete. As I

walked down the company street one day, I heard a radio announcer, from

inside one of the tents, report that the U.S. had dropped an atomic

bomb on Japan. One of the voices from within said “what the hell

is an atomic bomb”? I too wondered! A few days later, after

the second bomb was dropped, our unit was disbanded and most of

us transferred, again, to other units to prepare for return

home and discharge from the service

The 82nd

Engineer Combat Battalion, after returning its high point men to

the states, was assigned to Camp Miles Standish, Massachusetts and

formally de- activated in November 1945

.

|

| One more enemy to

defeat! The seeds of war now wither on the vine! During the summer of 1945, development of the atomic bomb and the subsequent bombing of the Japanese cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki ended plans for the invasion of Japan, and concluded World War II! The story behind President Harry S. Truman’s decision to order the bombings would not be revealed officially for almost a half century. Finally, more than 40 years later, the facts were unveiled when secret documents at Washington were finally declassified. The report, labeled "Operation Downfall," revealed that the invasion of Japanese Islands would involve more than 40 percent of American servicemen still in uniform. With exception of parts of the British Pacific Fleet, Operation Downfall, was to be an American effort. The invasion was set to begin on Nov. 1 1945. The data included grim projections provided by Gen. Douglas MacArthur’s chief of intelligence, indicating more than 250,000 Americans would be lost on the island of Kyushu, alone. There, American ground troops would be outnumbered by thousands of the elite and well-fortified, kamikaze troops of the Japanese Home Army. On July 26, the United Nations issued the Potsdam Proclamation, which demanded uncontitional surrender or face "total destruction.’’ Four days later-- the Japanese government broadcast to the United States and to the world that it would not surrender! After the Japanese refusal to surrender, President Truman authorized use of the atomic bomb. The United States dropped atomic bombs, first on Hiroshima, on Aug. 6, 1945, and -- when Japan still failed to surrender -- a second bomb was dropped on Nagasacki. These bombings led to the end of war. Japanese leaders accepted terms of unconditional surrender eight days later, on Aug. 14, 1945. After six grueling years, the greatest war in the history of the world was finally over! |

| 82nd’s

Epilogue Of the 664 men who landed at Omaha Beach, 160 became casualties. Twenty four were were dead, two missing in action, three prisoners of war and 134 men had been wounded, many seriously ---During the ten and one half months of combat, the 82nd was attached or supported the 29th, 30th, 35th, 8th, and 104th Infantry Divisions the 2nd, 3rd, and 7th Armored Divisions and the 113th Cavalry Group. ---Served as front line Infantry ---Laid 2600 and removed 2800 mines and booby traps. ---Constructed 26 bridges total length of 2200 feet and removed 7 bridges ---Distributed over 2,500,000 gallons of water ---Destroyed 145 pillboxes ---Used over 64,000 pounds of explosives ---Used dozers and equipment other equipment for over 2000 hours to: - Remove 105 roadblocks - Dug 105 gun emplacements - Removed 84 vehicles from main roadways - Bury 142 head of livestock - Laid over 6000 feet of concertina wire and 5200 feet of snow fenc ---To keep supply lines open trucks hauled 16,000 loads of material, Over 40,000 tons! ---And along the way captured 469 of the enemy! ______________________________________ The battalion received three Unit Citations The French Croix de Guerre - for the liberation of Vire France, August 1944 The Belgium Fourragere - for action along the Muse River (Albert Canal), September 1944 The Presidential Unit Citation - for action at the Elbe River, April, 1945 8 Men received Silver Stars 55 received bronze stars __________________________ |

| After the War

On November 21, 1945, the 82nd Engineer Combat Battalion WWII was

formally deactivated at Camp Miles Standish. The follo - ing year

the 82nd was reactivated, but this time redesignated as the 1092

Engineer Combat Battalion. The 1092nd, a unit of the West Virginia

National Guard, fought in Korea and has since been deactivated.

Then on January 30, 1947 the 82nd designation was reborn as the army re-designated the former 39th Combat Engineers, who had served in Italy during WWII, as the 82nd Engineer Battalion. This second generation 82nd Engineer Battalion served during the Berlin build-up in 1961, Desert Storm in 1991, deployed to Bosina in 1998 and later assigned as a unit of the United States 1st Infantry Division in Bamberg Germany. This battalion was also deactivated in March 2006 during ceremonies at Bamburg Barracks, Germany. Although the 82nd Engineer Combat Battalion exists only as a file in some remote United States Army hall of records, the exploits of the 82nd Engineer Combat Battalion and its successors, lives on in the memories of those who served! |